For the first time in their party’s four-decade history, the German Greens have announced a candidate to run as chancellor.

Equally historic is the central role the Greens will play in September’s general election.

On Monday, the Green Party announced that 40-year-old Annalena Baerbock would be its choice to take over from Angela Merkel after September’s election. Ms Baerbock is likely to be the only woman in the race.

Once seen as a chaotic bunch of bearded hippies in sandals, the Greens are now likely to enter the next government.

With the conservatives in chaos amid rows over their candidate, the Green Party could even end up the largest in the new coalition. That would mean Annalena Baerbock would be Germany’s next chancellor.

She’s already being compared to young female leaders in New Zealand or Finland.

Ms Baerbock was born in 1980, the same year that the party was founded. Her parents took her on anti-nuclear demos. She describes her childhood as a mixture of water cannon at protests, and cake at home later – a mix of cosy middle-class radicalism that sums up the Green Party today, and explains its current mass appeal.

According to the most recent poll, the Greens have 22% of the vote, second only to Angela Merkel’s conservative CDU/CSU bloc.

The conservatives have slumped from over 40% in the summer, when Germany was faring relatively well in the pandemic, to 29%. In some polls the conservatives score even less, putting them a mere four or five percentage points ahead of the Greens.

The centre-left SPD has been hovering in the mid- to upper-teens for months. All the other parties are stuck around, or just under, the 10% mark.

To make matters worse for the CDU/CSU, the appalling poll numbers don’t yet take into account the latest row within the conservatives about their own candidate for chancellor.

While the conservative alpha males have been busy tearing themselves apart in an unedifying scramble for power, the Greens quietly got on with choosing their candidate for the top job. With a Kremlin-like secrecy, nothing leaked out until the formal decision on Monday.

The new Green leadership has developed an iron grip on party discipline and a thirst for power that Bismarck would have been proud of.

But things haven’t always been harmonious in the Green Party. Traditionally the conservatives are disciplined and the Greens the chaotic ones.

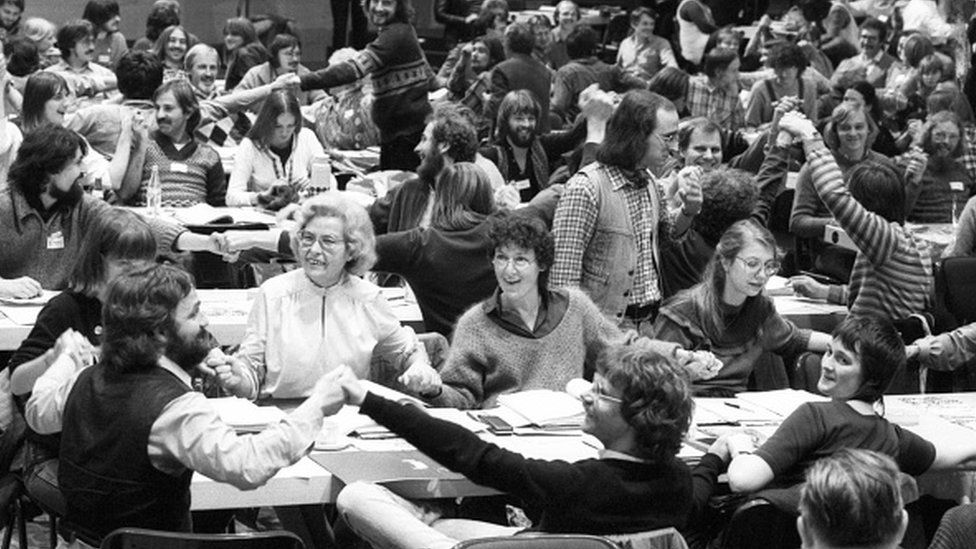

Television footage of the party’s founding ceremony looks like a student union meeting, with shaggy-haired young people in hemp shirts and knitted waistcoats shouting passionately.

For most of its history the party has been riven by divisions between “Realos”, or realists, who believe mainstream society needs to be won over, and “Fundis”, or fundamentalists, who view any compromise as a sell-out.

In 1998 the Greens entered into their first national governing coalition, as junior partner to the centre-left SPD. The new Green foreign minster, Joschka Fischer, was asked by sniggering journalists whether muesli-eating would be made compulsory.

The “Realos” had won – but the battles intensified with the compromises that came with power. In 1999 Mr Fischer was pelted on the head by a bag of red paint at a party conference when he said the Greens would support Nato air strikes in Kosovo.

The rows continued for decades, leaving the Greens divided and in the political wilderness nationally.

But pragmatic and successful leadership in powerful regional governments showed the Greens could rule effectively.

In 2011 the wealthy state of Baden-Württemberg voted in Germany’s first regional Green premier, Winfried Kretschmann. With a mix of economic pragmatism and environmental conviction, he has stayed in power and remained popular.

Three years ago the party voted for Ms Baerbock and Robert Habeck as joint party leaders – both “Realos” but with an impressive knack of bringing the two wings together. As the Greens’ poll numbers soared, opposition faded away.

But their march on power won’t be easy.

The Greens often over-poll and underperform. Voters like to sound virtuous and say they’ll vote Green. But when it come to election day, traditional loyalties and pragmatic concerns over the economy kick in.

The Greens will also be in the firing line from all sides. The left will call them elitist bourgeois who care more about drinking soy lattes than workers’ rights. The right will raise the spectre of preachy moralists who want to ban German cars and sausages.

But after 16 years of a distinctly green-tinged Chancellor Merkel – she is phasing out nuclear and coal – Germany has changed. The mainstream is greener, and the Green Party is more mainstream. So anti-Green clichés seem dated, and could insult voters.

Either way, the Greens are focused on power. No-one is making jokes about muesli anymore.