Eight-year-old Devanshi Sanghvi could have grown up to run a multi-million dollar diamond business.

But the daughter of a wealthy Indian diamond merchant is now living a spartan life – dressed in coarse white saris, barefoot and going door-to-door to seek alms.

Because last week, Devanshi, the elder of the two daughters of Dhanesh and Ami Sanghvi, renounced the world and became a nun.

The Sanghvis are among 4.5 million Jains who follow Jainism – one of the world’s oldest religions, which originated in India more than 2,500 years ago.

Religious scholars say the number of Jains renouncing the material world has been rising rapidly over the years, although cases involving children as young as Devanshi are uncommon.

Last Wednesday’s ceremony in Surat city in the western state of Gujarat, where Devanshi took “diksha” – vows of renunciation – in the presence of senior Jain monks, was attended by tens of thousands.

Accompanied by her parents, she arrived at the venue in the city’s Vesu area, bejewelled and dressed in fine silks. A diamond-studded crown rested on her head.

After the ceremony, she stood with other nuns, dressed in a white sari which also covered her shaved head. In photographs, she is seen holding a broom that she would now use to brush away insects from her path to avoid accidentally stepping on them.

Since then, Devanshi has been living in an Upashraya – a monastery where Jain monks and nuns live.

“She can no longer stay at home, her parents are no longer her parents, she’s a Sadhvi [a nun] now,” says Kirti Shah, a Surat-based diamond merchant who is a friend of the family and also a local Bharatiya Janata Party politician.

“A Jain nun’s life is really austere. She will now have to walk everywhere, she can never take any kind of transport, she’ll sleep on a white sheet on the floor and cannot eat after sundown,” he added.

Sanghvis belong to the only Jain sect that accepts child monks – the other three admit only adults.

Devanshi’s parents are known to be “extremely religious” and Indian media has quoted friends of the family as saying that the girl was “inclined towards spiritual life since she was a toddler”.

“Devanshi has never watched television, movies or gone to malls and restaurants,” the Times of India reported.

“From a young age, Devanshi has been praying thrice a day and even performed a fast at the age of two,” the paper added.

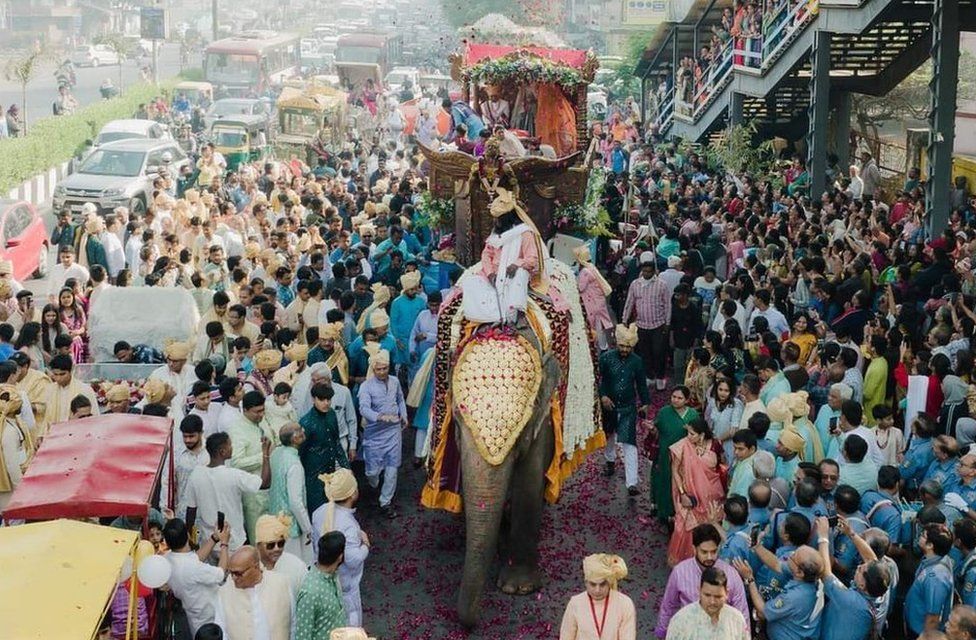

A day before her renunciation ceremony, the family had organised a huge celebratory procession in Surat.

Thousands watched the spectacle as camels, horses, ox carts, drummers and turbaned men carrying canopies walked the streets, with dancers and performers on stilts providing entertainment.

Devanshi and her family sat in a chariot pulled by an elephant, while crowds showered them with rose petals.

Processions were also organised in Mumbai and the Belgian city of Antwerp, where the Sanghvis have businesses.

Even though there’s support from within the Jain community for the practice, Devanshi’s renunciation has led to a debate, with many asking why the family couldn’t wait for her to reach adulthood before making such important choices on her behalf.

Mr Shah, who was invited to the diksha ceremony but stayed away because the idea of a child renouncing the world makes him uncomfortable, insisted that “no religion should allow children to become monks”.

“She’s a child, what does she understand about all this?” he asked. “Children can’t even decide what stream to study in college until they are 16. How can they make a decision about something that will impact their entire life?”

When a child renouncing the world is deified and the community celebrates, it can all seem like a big party to her, but Prof Nilima Mehta, a child protection consultant in Mumbai, says the “difficulty and deprivation the child will go through is immense”.

“Life as a Jain nun is very very tough,” she says.

Many other community members have also expressed unease at a child being separated from her family at such a young age.

And since news broke, many have taken to social media to criticise the family, accusing the Sanghvis of violating their child’s rights.

Mr Shah says the government must get involved and stop this practice of children renouncing the world.

But it’s not very likely to happen – I reached out to the office of Priyank Kanungo, chief of the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR), to ask if the government was going to do anything about Devanshi’s case.

His office said he did not want to comment on the issue because it’s a “sensitive matter”.

Activists, however, say that Devanshi’s rights have been violated.

To those saying that the child is turning ascetic “out of her own free will”, Prof Mehta points out that “a child’s consent is not consent in law”.

“Legally 18 is the age where someone makes an independent decision. Until then a decision on her behalf is made by an adult – such as her parents – who has to consider whether it’s in her best interest.

“And if that decision deprives the child of education and recreation, then it is a violation of her rights.”

But Dr Bipin Doshi, who teaches Jain philosophy at Mumbai University, says “you cannot apply legal principles in the spiritual world”.

“Some are saying a child is not mature enough to take such decisions, but there are children with better intellectual capabilities who can achieve much more than adults at a young age. Similarly, there are children who’re spiritually inclined, so what is wrong if they become monks?” he asks.

Besides, Dr Doshi insists, Devanshi is not being harmed in any way.

“She may be deprived of the traditional entertainment, but is that really necessary for everyone? And I don’t agree that she’ll be deprived of love or education – she’ll receive love from her guru and she will learn honesty and non-attachment. Is that not better?”

Dr Doshi also says that in case Devanshi changes her mind later on and thinks that “she took a wrong decision under the mesmerising effects of her guru”, she can always return to the world.

Then why not let her decide when she’s an adult, asks Prof Mehta.

“Young minds are impressionable and in a few years, she may think this is not the life she wants,” she says, adding that there have been cases where women have changed their mind once they have grown up.

Prof Mehta says a few years ago she dealt with the case of a young Jain nun who had run away from her centre because she was so traumatised.

Another girl who had become an ascetic at nine caused a scandal of sorts in 2009 after she turned 21 and eloped and married her boyfriend.

In the past, petitions have also been filed in court, but Prof Mehta says any social reform is a challenge because of the sensitivities involved.

“It’s not just among Jains; Hindu girls are married to deities and become devadasis [though the practice was outlawed in 1947] and little boys join akhadas [religious centres], in Buddhism children are sent to live in monasteries as monks.

“Children are suffering under all religions, but challenging it is blasphemy,” she says, adding that families and societies need to be educated that “a child is not your possession”.