Intel has launched its latest desktop PC chips having had to retrofit some of its recent semiconductor designs to work on older transistor tech to deliver the processing power required.

The stopgap effort has consequences for both the speeds and heat they produce.

The US firm claims the Rocket Lake chips deliver a 19% headline-rate gain over the last generation, and introduce features that will help PCs keep pace with the latest gaming consoles.

Intel continues to dominate the sector.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/68652121/Screen_Shot_2021_01_11_at_3.46.12_PM.0.png)

But rivals have benefited from outsourcing production, leading to suggestions that Intel’s position as the leading CPU (central processing unit) provider is not as secure as it might appear.

Tiny switches

Transistors are basically tiny on-off switches, and billions of them are arranged in different patterns to carry out calculations on a chip.

The benefit of making them smaller is that more can be packed into the same space – allowing computers to run more quickly while potentially using less power.

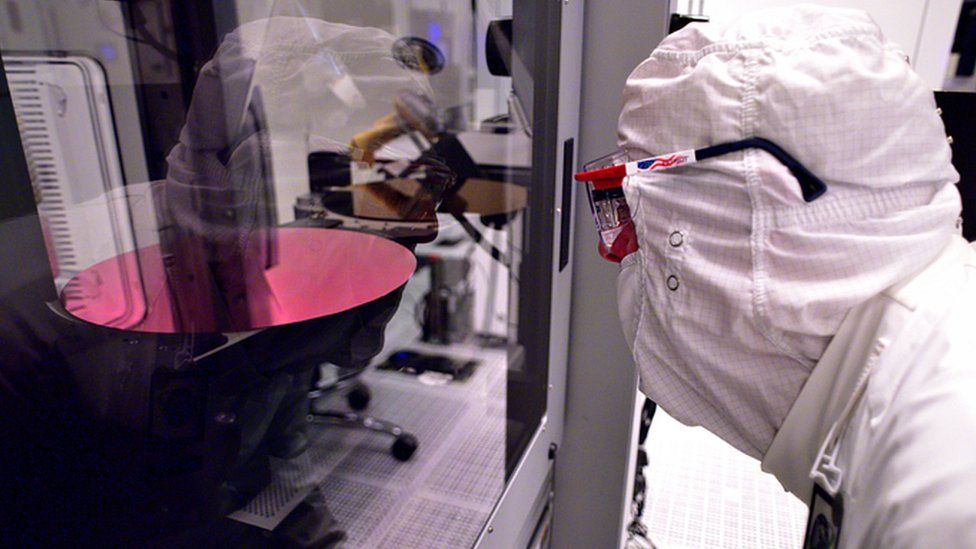

Intel’s new Rocket Lake chips rely on 14 nanometre transistors, and are made within its own fabrication plants.

By contrast, its chief competitor AMD uses a contract manufacturer – Taiwan’s TSMC – to build its latest Ryzen desktop PC chips, which benefit from smaller 7nm transistors.

And Apple is in the process of weaning itself off Intel to use its own designs, also produced by TSMC but using its even more advanced 5nm tech.

Fab-less pressure

There is no set way to measure transistor sizes, and Intel claims its 14nm tech equates to TSMC’s 10nm. Even so, the US firm acknowledges it is running behind.

It had originally intended to make the transition to 10nm desktop chips between 2017 and 2019. As it is, this will not happen until a future generation launched in late 2021-2022.

And Intel is also experiencing delays in making the next leap forward to 7nm.

However, there are advantages to keeping production in-house.

It helps keep costs down.

And it also means it avoids feeding into wider concerns that the US has become over-reliant on overseas chip-producers.

Intel recently appointed a new chief executive – Pat Gelsinger – who has made it clear he intends to resist pressure from some investors to become a “fab-less” firm, a term used to refer to chip designers who do not operate fabrication plants of their own.

“The factory is the power and soul of an enterprise, and we must become even better in the future,” said Mr Gelsinger in January.

Faster frame rates

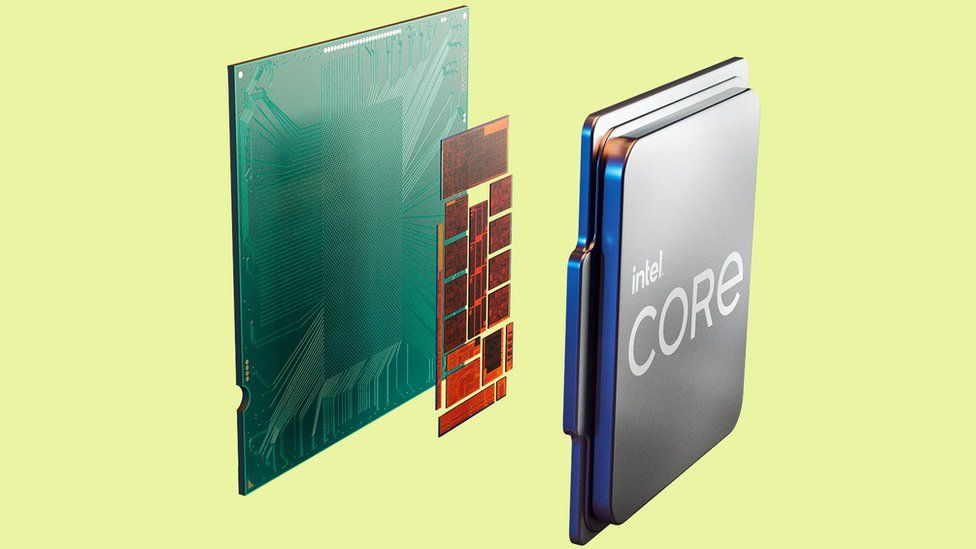

The new “11th generation” desktop chips take the microarchitecture for their CPU cores from one set of 10nm laptop chips – 2019’s Ice Lake series – and their graphics architecture from another – 2020’s Tiger Lake family.

Intel has described the process of reworking these designs for 14nm transistors as “backporting”.

“We’ve been making 14nm CPUs for a long time, and part of the benefit of that is it is a very established manufacturing process to the point where we know it inside and out,” spokesman Mark Walton explained.

“So we really know how to ramp up the clock speeds – and for a gaming product, that’s really, really important.”

The firm’s own benchmarks indicate its new i9-11900K chip will deliver a boost of 14% more frames-per-second when playing Microsoft Flight Simulator over the last-generation i9-10900K, when set at high quality graphics, for example.

And Intel is also playing up other benefits, including support for PCie 4.0, which increases the bandwidth available to third-party components such as add-on graphics cards and solid state drives, effectively allowing them to shunt data about more quickly.

“You will have much faster loading times, textures will load more quickly in games, and you get a much more seamless experience,” said Mr Walton, suggesting this would counter one of the key advantages the Xbox Series X and PlayStation 5 enjoyed.

Testing hot

Intel will be marketing the new chips as offering a 19% improvement in “instructions per cycle” over their predecessors.

But the site Anandtech said it had only noticed modest gains when testing some of the chips with games of its own choice, and in some cases said the differences were imperceptible.

“It trails behind its competitor AMD at times by a significant margin,” the site’s Dr Ian Cutress told the BBC.

Moreover, the review also highlighted that the chips could run very hot.

Intel has removed a very thin layer of material between the block of semiconducting material on which the CPU’s circuits are fabricated and the “heat spreader” on top to help keep the components cool.

But Anandtech recorded peak temperatures of 104C (219F) in one of its tests, which is only just in the safety zone.

“Intel’s laptop chips were designed specifically for the characteristics of 10nm, and that includes thermal performance and frequency, and voltage,” explained Dr Cutress.

“Because they’ve done a retrofit, compromises have had to be made – they still get the performance gains, but it’s at the expense of needing lots of power and potential heat issues.”

In real-world terms, that means if users give the chip taxing tasks and do not have proper cooling, the chip may throttle its own performance to avoid damage.

One added consequence is that Intel is only offering Rocket Lake chips with a maximum of eight cores – the more cores you have the faster a program can run if optimised to share the load between them.

By contrast, AMD’s Ryzen chips go up to 16.

However, AMD’s newest processors remain in short supply.

And one advantage Intel has as its own manufacturer, is that it can relatively easily adjust production to match demand.

By contrast, AMD must vie with Apple, Nvidia and others for TSMC’s capacity.