A mission will launch to space this weekend that aims to demonstrate commercial technology to remove orbital debris, such as a defunct satellite.

The showcase is being staged by the Astroscale company and will be run from an operations centre in the UK.

With more and more satellites being launched every year, there is now an imperative to try to keep orbits above the Earth clear of old junk.

And this ought to drive a vibrant market for debris removal services.

“We are entering an age of satellite constellations and some of these spacecraft could fail in orbit – and that would be a serious issue,” said John Auburn, Astroscale’s UK managing director.

“If they fail at very low altitudes, they’ll come back down on their own; but if satellites fail at 1,200-1,300km in altitude – they’ll be up there for centuries with the risk that they start to break up, collide with other objects and make the debris situation much, much worse.”

The End-of-Life Service by Astroscale demonstration (Elsa-d) mission consists of two spacecraft: a 175kg “servicer” and a 17kg “client”.

They’ll go up together on a Soyuz rocket on Saturday from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan and, once in orbit, separate to play a repeating game of cat and mouse.

The servicer will use its sensors to find and chase down the client, latching on to it using a magnetic docking plate, before then releasing “the mouse” for another capture experiment.

The task will become increasingly complex, with the most difficult rendezvous requiring the servicer to grab the client as it’s tumbling.

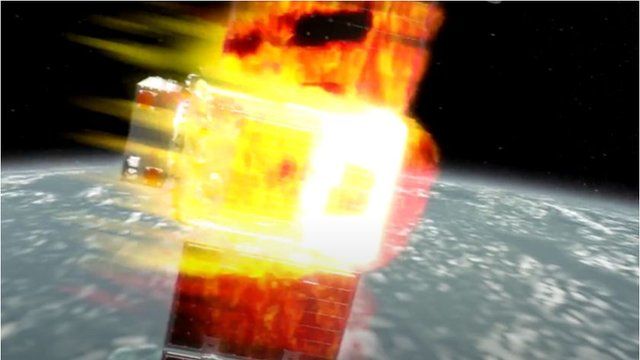

Ultimately, the duo will be commanded to come out of orbit to burn up in the atmosphere.

The Elsa-d demonstration will be overseen from a control centre at the UK’s Satellite Applications Catapult in Harwell, Oxfordshire.

The centre will be tied into a network of 16 ground stations to maintain continuous communications with the experimental spacecraft.

The Harwell facility has been funded by the UK government, which wants to make Britain a hub for businesses that can service and/or remove ageing satellites, and generally play into what is termed space domain awareness. This includes object tracking and traffic management.

The capabilities were highlighted in the government’s “Integrated Review” of strategic thinking published on Tuesday.

There are more than 3,000 working satellites in orbit currently, with thousands more scheduled to go up this decade.

The space environment, however, is becoming increasingly cluttered. Alongside the working satellites are something like 9,000 tonnes of discarded, uncontrollable hardware – all of it a potential collision risk to operational systems.

International best practice calls for redundant hardware to be brought down within 25 years of mission cessation. But compliance is generally poor. A report in January from the US space agency’s Office of Inspector General said the guideline had been met in only 20-30% of cases over the past decade.

Compliance had to improve, said Dr Alice Bunn, the UK Space Agency’s international director.

“I liken it to the M25 (orbital motorway) around London. Imagine if every time there was an accident and no-one came to clear away the debris – and, even worse, the debris continued to circulate around the motorway, creating a risk of further collisions. That’s the situation we’ve had in space,” she told BBC News.

The idea of a commercial market for removal services has been discussed for many years. But there are now signs that they should become a reality.

The American aerospace giant Northrop Grumman is sending what it calls Mission Extension Vehicles to go and rendezvous with low-on-fuel satellites. These MEVs are designed to take over the manoeuvring duties of ageing spacecraft.

Swiss company ClearSpace has been contracted by the European Space Agency to run its own debris-removal experiment in 2025. This will see a giant claw grab discarded rocket hardware.

OneWeb, the broadband satellite constellation that was recently part-purchased by the British government, is putting an Astroscale-compatible docking plate on all its new spacecraft just in case they experience an in-orbit failure in the future and need to be collected by a servicer vehicle.