The US has a vast system of detention sites scattered across the country, holding more than 20,000 migrant children. Special investigation has uncovered allegations of cold temperatures, sickness, neglect, lice and filth, through a series of interviews with children and staff.

It was midnight on the Rio Grande – the imposing river that forms the border between Texas and Mexico – and lights began to flash on the Mexican side. Voices could be heard in the darkness. Figures emerged, got into a small raft, and began to cross the river.

As the raft appeared on the US side, the faces of the migrants became visible. More than half of them were children. Over March and April, more than 36,000 children crossed into the US unaccompanied by an adult. This was a record high for recent years.

Many children travelling alone set out on their journey hoping to reunite with a parent already in the US. More than 80% of them already have a family member in the country, the US government says.

President Joe Biden has opened the border to unaccompanied children seeking asylum, somewhat relaxing former President Trump’s policy of turning migrants away due to Covid-19.

The children scrambled up the banks, exhausted. Two young cousins held hands. Another youth, Jordy, 17, said he had fled Guatemala because he was afraid of violent gangs operating there. But tonight he was frightened about what might await him in migrant detention centres in the US. He said he had heard stories about them.

“They will put us in an icebox and ask us questions,” he said.

The so-called “iceboxes”, notorious among migrants, are extremely cold rooms or cubicles in US Border Patrol migrant processing facilities.

Jordy was told to join a line with other children. US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) guards were taking the children’s shoelaces and belts, a process usually reserved for prisoners to prevent them trying to take their own lives.

Jordy and the other children were then taken away by bus into the night. They were to join more than 20,000 migrant children now in US detention, held in a series of extensive camps around the country, at least 14 of which are new.

In late March, CBP released disturbing images of cramped conditions within one particular facility it runs in Donna, Texas – a mass of enormous white tents looming above the small town. The facility was designed to hold 250 people but housed more than 4,000 at peak occupancy.

Journalists have not been allowed to talk to the children inside. Instead we have been tracking down the children who have been released, to find out about conditions in US detention sites.

Ten-year-old Ariany, who crossed into the US alone, spent 22 days in detention this spring, most of them in the Donna camp. She was crammed into a plastic cubicle – as were scores of other children, from toddlers to teens – wrapped in a silver emergency blanket.

“We were very cold,” she said. “We had nowhere to sleep so we shared mats. We were five girls on two mats.”

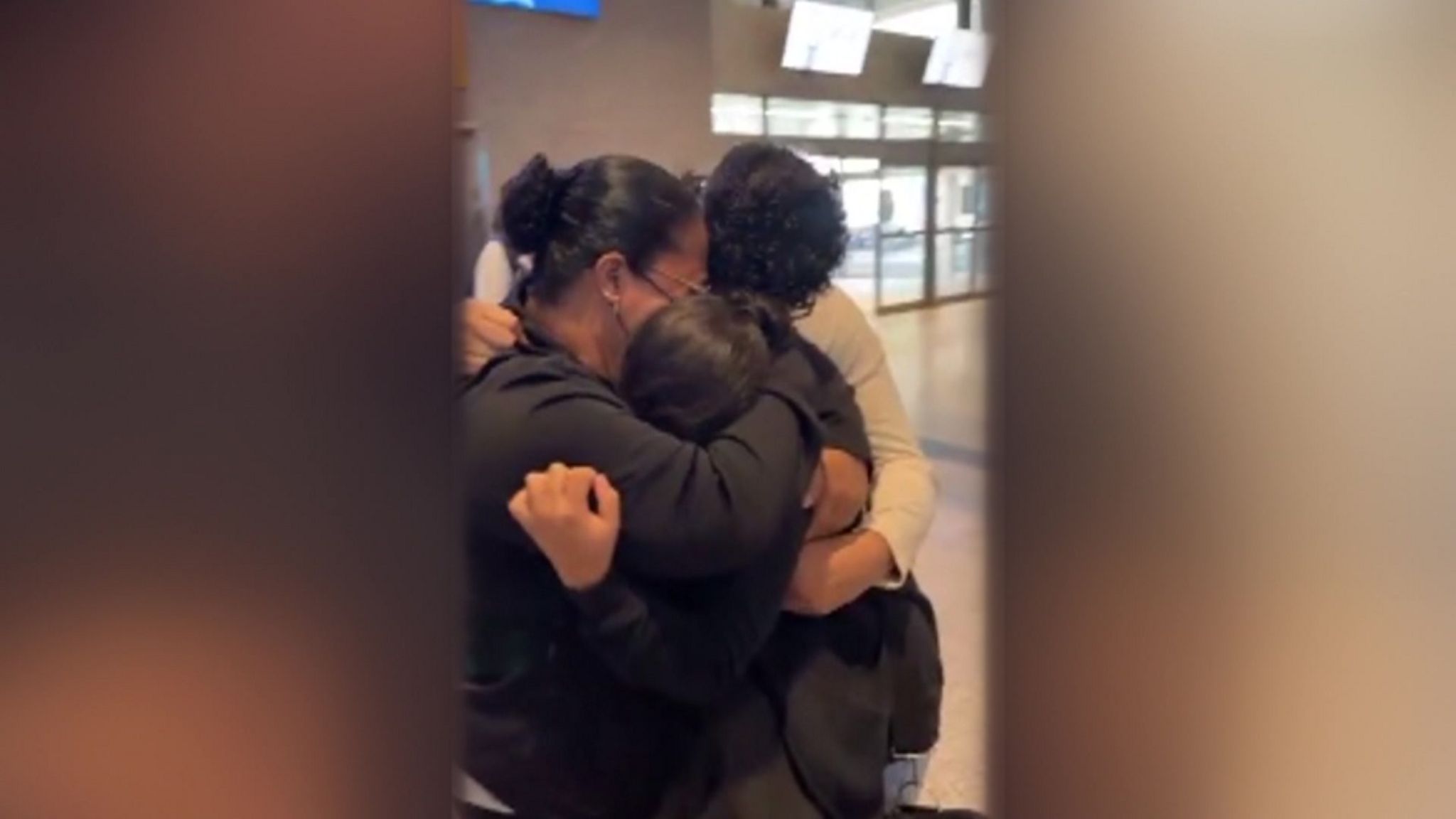

Ariany was finally reunited with her mother, Sonia, in late March.

She had passed her mother’s contact details onto US officials who were able to locate her. Sonia had fled Honduras six years ago with her son due to gang violence, leaving Ariany – who was too young at the time to make the journey – behind with her older sister.

Cindy, 16, also held in Donna this spring, said there were 80 girls in her cubicle and that she and most of the children were wet under their blankets, due to dripping pipes.

“We all woke up wet.” She said. “We slept on our sides, all hugged, so we stayed warm.”

A number of children, including Ariany and Paola, a 16-year-old also released from Donna, told media that they were given food that had expired, or was rotten or not cooked properly.

They told us that many children became sick.

“Some girls fainted,” said Jennifer, who was 17 at the time of her detention.

Some girls in Donna were able to shower once a week, but others said they did not shower for several weeks at a time. Paola struggled with the filth.

“I started to feel my head itching, and I realised that it was not normal. They checked my head and told me that I had lice.”.

With children eating and sleeping in close quarters, the cubicles quickly became rancid. Ten-year-old Ariany said the guards threatened the children if they did not keep their cramped quarters clean.

“Sometimes they would tell us that if we were doing a lot of mess, they were going to punish us by leaving us there more days,” she said.

At night, the children said, the tents were filled with the sounds of crying.

“We all cried, from the youngest up. There were two-year-old, or one-and-a-half-year-old babies, crying because they wanted their mother,” said Cindy.

Paola said she tried to help the younger ones, but was also worried that she herself would never be reunited with her mother.

“They cried in front of me, and I just tried to comfort them and tell them that one day we would get out of there – although sometimes inside me I had doubt, because [the staff] would not ask me for my mom’s number, her address, and I felt bad too,” she said.

Flights moving thousands of children

And then one day Cindy began to deteriorate and feel ill. She tested positive for Covid-19, as have a startling number of migrant children in detention. Health and Human Services (HHS) reports more than 3,000 coronavirus cases among migrant children in Texas alone since last year. It is not known what the total number of cases is in the new emergency detention sites around the country.

Eventually Cindy, without being told where she was going, was transferred with 40 other Covid positive children onto bus, then plane, and flown 2,400km (1,500 miles) away to San Diego, California. They were taken to a new detention site – a convention centre with the capacity for almost 1,500 children – with row after row of flimsy camp beds.

She says she was kept away from the healthy children, in a section full of children with Covid. She said conditions were better than at Donna, but it was still days before she was able to shower.

Who are the children?

- Persecution, gang violence and organised crime, losses from natural disasters (including two Central American hurricanes in 2020), and poverty are all causing parents to send their children to seek refuge in the US. Migrants are vulnerable to exploitation and sexual abuse along the way

- Most are teenagers from Guatemala, Honduras or El Salvador, though some are reported to be as young as six or seven

- They are either sent by relatives on their own, or with people smugglers who charge thousands of dollars, though reports suggest some families accompany the children to the border and then send them across alone to improve their chances of US entry

- Most have family members already in the US, about half of whom are a parent

- Only 4.3% of unaccompanied minors seeking asylum have been deported since 2014

Every day, flights leave US border towns loaded with children.

“On some days we estimate that hundreds of children are being transported around the country on these flights,” said Thomas Cartwright, of Witness at the Border, an organisation that logs the flights.

In the past few weeks, the authorities have moved about 3,000 children out of the Border Patrol facility in Donna, transporting many to a new network of child detention centres around the country run by HHS, including the one Cindy was transferred to in San Diego.

There are at least 14 such facilities, known as Emergency Intake Sites, on military bases, convention centres, or arenas in major US cities. These are a new part of a network of 200 detention centres for migrant children spread across 22 states.

This means that Donna is far less crowded now, with the camp holding around 300 children. The facility is being expanded, as the influx of migrants across the border continues.

One of the new Emergency Intake Sites is the Kay Bailey Hutchinson conference centre in central Dallas, which has 2,270 camp beds set up in a grid system in a huge hall, and held hundreds of teenage boys, aged 13-to-17, at its peak.

Staff who work in the Dallas site say they have had to sign non-disclosure agreements specifying they are not to talk about what goes on inside.

Children ‘contemplating suicide’

But some agreed to talk to us on condition of anonymity.

“The children always complain about not having enough, not eating enough,” one staff member said.

He also said the convention hall was cold, the boys had one thin blanket each, and were made to stay by their camp beds almost all day.

“Boys have been in there for 45 days straight with no sunlight, no recreation outside, no fresh air, no nothing,” said the staff member.

He said that the boys were only given 30 minutes of recreation twice a week in an indoor room and many had been in the convention centre for weeks.

“They are all depressed. I heard the other day that several were contemplating suicide because of the conditions here.

“They are being treated like prisoners, like inmates,” he said. “It’s haunting that this centre has not been able to meet the minimal standards of caring for unaccompanied minors.”

In response to the allegations of neglect of migrant children in the new detention sites, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) said: “The children are provided a safe and healthy environment with access to nutritious food, clean clothes, comfortable beds, education, recreational activities, and medical services.”

“The Dallas EIS (Emergency Intake Site) is providing required standards of care,” the statement said.

“The entire administration is working together to reduce the length of time children are in federal custody by making unifications our top priority,” it added, pointing out that the number of children in the care of the HHS has more than doubled.

Children are being released regularly, but for many it is a very slow process. The average time in detention in the emergency centres is a month.

The largest Emergency Intake Site is a tented facility at the Fort Bliss military base in El Paso, Texas, holding more than 4,500 children in the searing desert. It has a capacity for more than 10,000.

A source inside has told the BBC that some of the tents contain 500-800 girls and boys who sleep in long rows of bunks. The source said hundreds of children are in Covid isolation, and that there are designated tents at the site now for scabies and lice, of which there are also outbreaks. Sources say the living conditions are unsanitary, and that there has been at least one report of sexual abuse in the girls’ tent. An official document indicates children under six may be sent to Fort Bliss.

The HHS did not respond to a request for comment on these allegations.

Agony at the border

Amy Cohen, a psychiatrist based on the other side of the country in Los Angeles, has more than 30 years of experience working with traumatised children. She said the alleged conditions in the camps could be extremely damaging for those inside.

“Even after weeks in these conditions, many children are at greater risk of developing major psychiatric illnesses later in life, at greater risk of substance abuse and a greater risk of suicide,” she said.

Cohen said these migrant children would be even more vulnerable because many had been separated from a non-parental family member, or someone they came to rely on as a family member, at the border.

“If a child comes over with someone who is not their biological parent, even if they are their psychological parent, they are uniformly taken away from that individual, taken out of their laps, taken out of their arms, and called an unaccompanied minor.”

She also said parents were being forced to make the decision to separate themselves from their children, because families who are turned away often then send their children back across the border alone, rather than risk their welfare in dangerous cities along the Mexican border. There, she says, they are vulnerable to rape, trafficking and assault.

“So these parents, when they find they’re unable to protect their children, end up feeling forced to send their children by themselves across the river, in order to preserve their lives.”

Cohen said that although children were no longer being physically taken from their biological parents by border guards – as had happened for a time under former President Trump’s so-called “zero tolerance policy” – the process of family separation was deeply psychologically damaging.

“I interviewed children who were removed from parents under the Trump administration’s ‘zero tolerance’ policy… and I’ve interviewed many children who’ve been now taken away from aunts, and uncles, and siblings… I am seeing exactly the same trauma in these children now as we saw in those children then.”

The CPB told the BBC that under federal law any child arriving without a parent or legal guardian was considered unaccompanied and must be transferred to the HHS without the adult relative.

How Biden differs from Trump on migration

- Has suspended the Migrant Protection Protocols programme, also known as the Remain in Mexico policy, which required migrants to wait in Mexico while their cases were being heard by US immigration courts. Has gradually admitted those already enrolled in the programme to wait in the US while their cases are heard, while stressing that the border remains closed for others.

- Has created a taskforce to reunite families who were divided during Trump’s so-called “zero tolerance” policy

- Has paused construction on the Mexican border wall, and has proposed a major new immigration bill which would offer a pathway to citizenship for undocumented migrants already living in the US