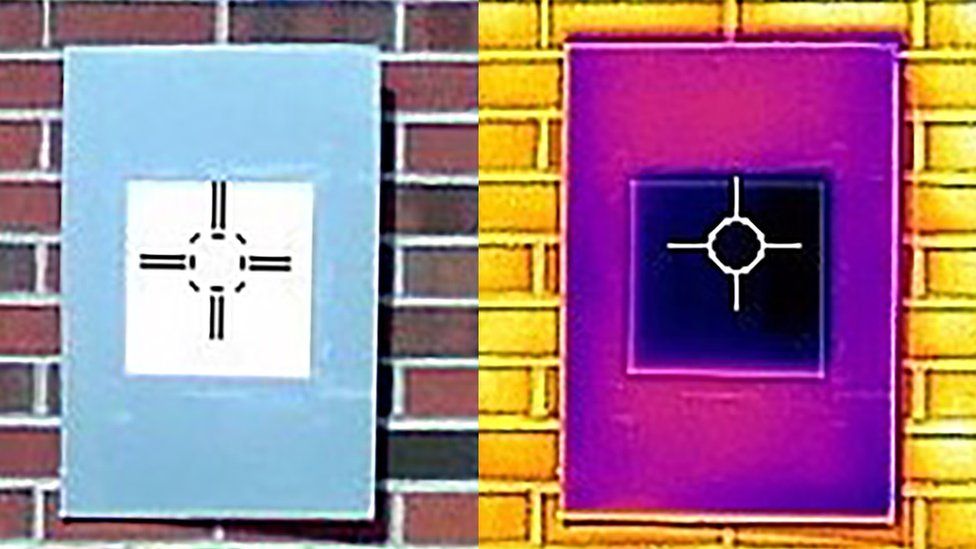

Scientists in the US have developed a paint significantly “whiter than the whitest paint currently available”.

Tests carried out by researchers at Purdue University on their “ultra-white” paint showed it reflected more than 98% of sunlight.

That suggests, the scientists say, that it could help save energy and fight climate change.

Painting “cool roofs” white is an energy-saving approach already being rolled out in some major cities.

Commercially available white paints reflect between 80% and 90% of sunlight, according to lead researcher Prof Xiulin Ruan from Purdue, in West Lafayette, Indiana. “It’s a big deal, because every 1% of reflectance you get translates to 10 watts per metre squared less heat from the Sun,” he explained.

“So if you were to use our paint to cover a roof area of about 1,000 sq ft (93 sq m), we estimate you could get a cooling power of 10 kilowatts. That’s more powerful than the central air conditioners used by most houses,” he said.

Could white paint help fight climate change?

“Cool” white roofs are seen as an easy, urban climate solution.

In the US, New York has recently coated more than 10 million sq ft of rooftops white. The state of California has already updated building codes to promote cool roofs.

Their benefits are still being investigated, but studies have shown they can reduce energy demands and create lower ambient temperatures. That has the added benefit of reducing the amount of water used for irrigation in cities.

“We did a very rough calculation,” said Prof Ruan. “And we estimate we would only need to paint 1% of the Earth’s surface with this paint – perhaps an area where no people live that is covered in rocks – and that could help fight the climate change trend.”

How was this paint made ‘ultra-white’?

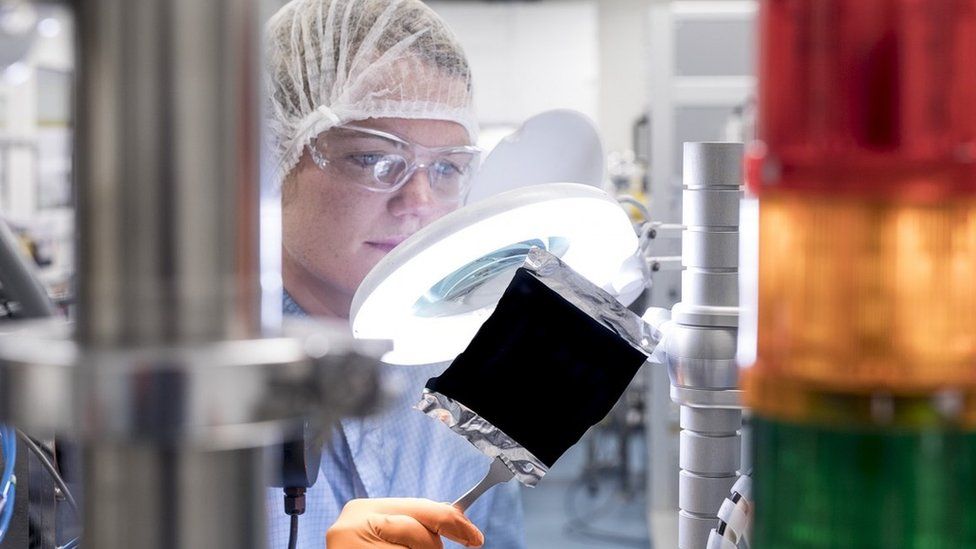

The new paint contains a compound called barium sulfate, which is also used to make photo paper and cosmetics.

“We used a very high concentration of the compound particles,” explained Prof Ruan. “And we use lots of different sizes of particles, because sunlight has different colours at the different wavelength.”

How much each particle scatters light depends on its size, “so we deliberately used different particle sizes to scatter each wavelength”.

Can anyone buy this paint?

The researchers are now working with a company to produce and sell their paint, which they say should be similar in cost to currently available paints.

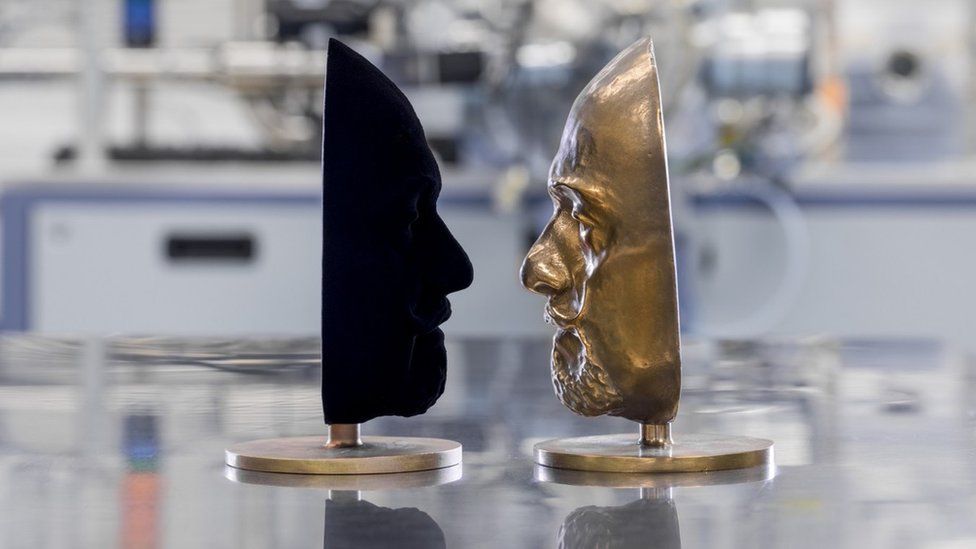

“I already had an inquiry from a museum that wants to put up a display of our whitest white paint side by side with the blackest black,” said Prof Ruan.

That ultra-black coating is a material scientists developed in 2014, called Vantablack.

It absorbs almost all light, so its potential uses are almost the opposite of the “ultra-white” paint. Vantablack, used in space telescopes, for example, could absorb stray light that might interfere with their ability to measure light from objects in deep space.

But Vantablack, which is a coating of nanoscale carbon tubes, is not available to everyone. Its invention led to an artistic controversy when sculptor and former Turner prize-winning artist, Anish Kapoor, bought the exclusive rights to its “use as an art material”.

In response, UK-based artist Stuart Semple created a pigment that he claimed to be the world’s “pinkest pink” and made it available to purchase on his website for “everyone but Anish Kapoor”.

Vantablack’s developers, a company called Surrey NanoSystems, said the exclusivity deal with Mr Kapoor would not preclude the whitest white being displayed alongside the blackest black in a museum. “That isn’t art; we would see it as an educational display for people interested in the science and technology behind extremes of light and darkness,” the company told BBC News.

Prof Ruan added that it would be up to the company that produces the “ultra-white” paint, but he hoped it would be available to everyone.